NMIBC - What is bladder cancer?

Worldwide, bladder cancer is the 10th most common cancer. It is a malignant disease of the urinary bladder. For a better understanding, a brief look into the function and structure of a healthy bladder is necessary.

The urinary bladder

Urine is produced in the kidneys and transported through two tubes (called ureters) to the urinary bladder. There, the urine is collected and released bulk wise. To fulfil this task, the bladder consists of muscular walls forming a flexible balloon embedded in the pelvis. A healthy adult bladder has a capacity of 300-350 ml.

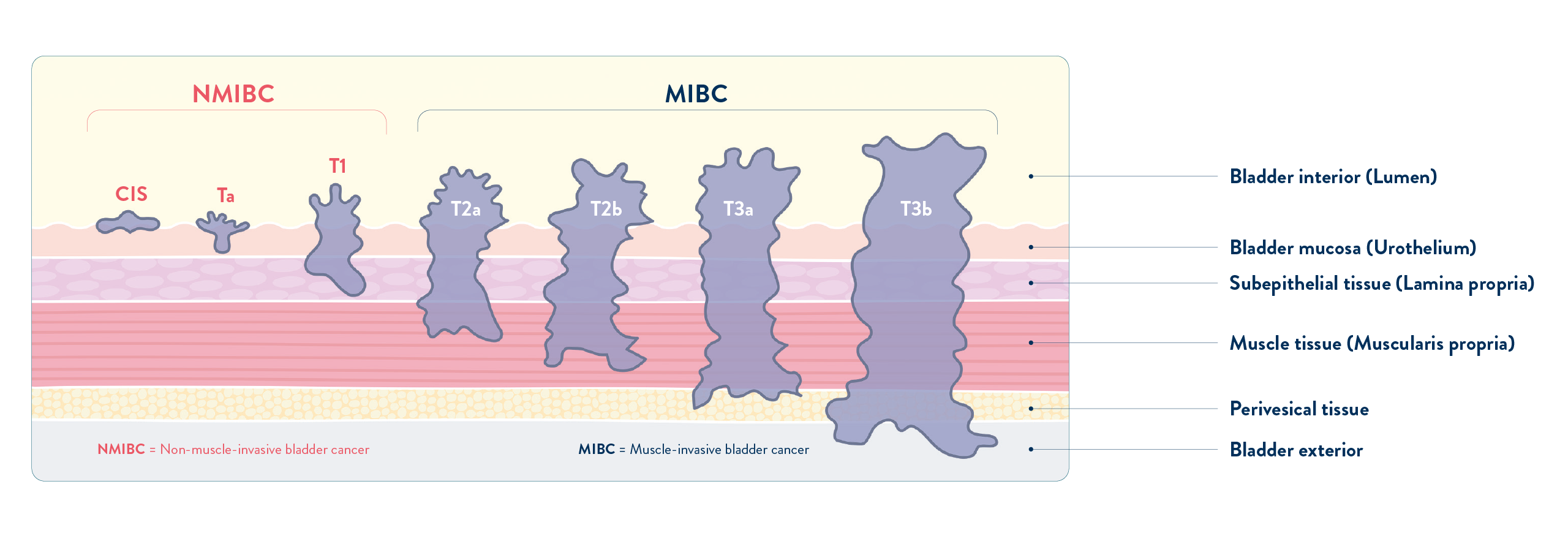

The bladder wall consists of 4 main layers:

- The inner lining is called the urothelium (epithelium of the urinary bladder). It consists of so-called urothelial cells.

- Beneath the urothelium lies the lamina propria, a thin layer of loose connective tissue that contains blood and lymph vessels, nerves and various other cell types. The so-called bladder mucosa consists of these two tissue layers: the urothelium and the lamina propria.

- A thick muscle layer, the muscularis propria, is enclosing the two inner layers.

- On the outer side, the bladder is separated from nearby organs by a layer of perivesical fat tissue.

LOG IN TO EXPLORE MORE

Learn more about NMIBC and therapy options

Bladder cancer

There are several types of bladder cancer. They are identified by their cellular origin, which is done by microscopic examination of tumour tissue samples. This distinction is important, as different cancer types show different pathological behaviour and need to be treated differently.

Urothelial carcinoma

Covering more than 90% of diagnosed bladder cancers, urothelial carcinoma is by far the most common subtype. Urothelial carcinomas develop from the urothelial cells on the inner surface of the bladder.

The whole urinary tract is lined by urothelial cells, starting from the renal pelvis, through the ureters, the actual urinary bladder and finally the urethra. Therefore, urothelial carcinoma can occur in all these places, not just the bladder. This means that the complete urinary tract needs to be checked in case of bladder cancer. The inner bladder surface covers the largest area within the urinary tract and has the longest exposure time to urine, that may contain carcinogenic substances, such as degradation products from cigarette smoke. Therefore, in most cases, urothelial carcinoma occurs in the bladder.

For prognosis and treatment, urothelial carcinomas are divided into two stages, depending on how far they have invaded into the bladder wall:

- Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancers have historically been called ‘superficial cancers’ of the urothelium which have not grown beyond the lamina propria. These tumours can be surgically removed at this stage, although recurrences are frequent. The purpose of post-operative intravesical therapy is to prevent or delay tumour recurrence (and progression).

- Muscle-invasive bladder cancers have grown into the muscle layer of the bladder or even beyond and are more likely to spread. At this stage, they are more difficult to treat.

A further division into NMIBC subtypes can be done according to the growth pattern of the tumour:

-

Papillary tumours grow coral-like from the inner bladder surface. Low grade Ta papillary tumours often grow toward the lumen of the bladder without invading deeper tissue layers. They tend to have a better outcome, compared to e.g. high grade T1 tumours

-

Flat carcinomas (Carcinoma in situ, abbreviated as CIS or Tis) are high grade tumours with a poorer outcome. Their growth is restricted to the urothelium, hence they do not project into the bladder lumen and are more difficult to detect.

Since most urothelial carcinomas develop in the urinary bladder, we will focus on this tumour type in the following chapters.

Risk factors for bladder cancer?

What are the risk factors for bladder cancer?

Risk factors can increase the probability of getting a specific disease like bladder cancer. Some risk factors can be reduced or avoided, like smoking. Others, like a person’s age or family history, are unchangeable. However, risk factors only indicate an increased likelihood of developing the disease and do not mean that an affected or exposed person will develop the disease. Conversely, the absence of risk factors does not provide complete protection against the disease. For example, not all smokers will develop bladder cancer. Similarly, there are bladder cancer patients who have never smoked.

Lifestyle

Smoking

Smoking is the most significant risk factor in the development and treatment of bladder tumours. A regular cigarette smoker has a 4-fold higher risk of getting bladder cancer compared with a non-smoking person. About half of all bladder cancers are caused by smoking habits.

Tobacco smoke contains carcinogens (cancer-causing substances) which are absorbed from the lungs and enter the bloodstream. They are filtered by the kidneys and excreted via the urine. These carcinogens may be detected in higher concentrations in the urine. At higher concentration, they can damage the cells lining the inside of the bladder over time, increasing the risk of cancer development.

Workplace Exposures

Various organic chemicals can cause bladder cancer by similar mechanisms to tobacco smoke. The following industries have shown to be associated with an increased risk: Manufacturers of paint products, rubber, leather, textiles as well as other industries, where the work force is exposed to carcinogenic chemicals. However, nowadays, good health and safety practices are in place so that these risks are minimised.

Patient Factors

Age

As for many other malignant tumours, the risk of getting bladder cancer increases with age. The average age of first diagnosis is 73. More than 90% of bladder cancer patients are older than 55.

Gender

The risk of getting bladder cancer is higher for men (approx. 3 to 4-fold) than for women.

Predisposition

Genetic predisposition

4.3% of bladder cancer patients were found to have a first-degree relative with bladder cancer, and up to 50% of urothelial cancer patients have a family history of cancer.

Personal History of Bladder Cancer

Cancer can form in all areas of the urothelium, comprising the innermost lining of the urine-collecting part of your kidney (renal pelvis), ureters, bladder, and urethra. Cancer developing in any of these locations can increase the risk of another tumour in this epithelial layer of cells (recurrence), regardless of the complete removal of the primary tumour. Bladder cancer patients need to be monitored closely following treatment because tumour recurrence in the urothelium is common.

Medical Factors

Chronic Bladder Irritations and Infections

Various causes of chronic bladder irritation, such as regular urinary infections, kidney and bladder stones and bladder catheters left in place over a long time have been linked to a special form of bladder cancer (squamous bladder cancer). However, it is unclear if they actually cause bladder cancer.

A locally specific risk factor for irritation-caused bladder cancer is schistosomiasis, an infection with a parasitic worm called Schistosoma hematobium. In countries where this parasite is common (Middle East and Northern Africa), squamous bladder cancer is occurring more frequently.

Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy

Long-term use of cyclophosphamide, a chemotherapeutic drug, is associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer. Drinking extra fluids while taking this drug can help protect the bladder from irritation and lower this risk. Radiation aimed at the pelvis is also considered a risk factor for bladder cancer.

Bladder Cancer risk factor summary1,2

-

Tobacco smoking

-

Occupational agents/chemicals (aluminium production, rubber manufacturing, dye industry, painter, firefighter, dry cleaning*, hair dressers/barbers*, printing processes*, textile manufacturing*)

-

Environmental factors (arsenic and inorganic arsenic compounds in drinking water)

-

Pelvic radiotherapy (X-ray and gamma radiation)

-

Outdoor air pollution*

-

Diesel exhaust*

-

Diseases (schistosomiasis)

-

Certain medications or drugs, such as chlornaphazine, cyclophosphamide, pioglitazone*, and opium consumption.

* limited evidence in humans

References

1 Jubber I, et al. Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer in 2023: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors. Eur Urol. 2023; 84(2): 176-190. PMID: 37198015.

2 International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). List of classifications by cancer sites with sufficient or limited evidence in humans. IARC monographs Vol. 1–132 .July 1, 2022. Available from URL https://monographs.iarc.who.int/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Classifications_by_cancer_site.pdf

Signs and symptoms

Blood in the urine

Usually, the first sign of bladder cancer is blood in the urine (haematuria). If the bleeding is strong enough it can change the colour of the urine, from orange over pink to red, depending on the amount of blood. If there are only small traces of blood, they need to be detected during urine testing, done as part of medical check-ups.

The blood might only be present sometimes, but in case of bladder cancer it eventually reappears. Early stages of bladder cancer often cause bleeding as the only symptom. However, blood in the urine does not necessarily indicate bladder cancer, but can also have other causes, such as urinary tract infection or kidney stones. Nevertheless, medical examination is important to rule out bladder cancer.

Changes in bladder function or symptoms of irritation

In addition to blood in the urine, there are other signs that may indicate bladder cancer:

- Increase in urination frequency

- Pain or burning during urination

- Urge to urinate, even when the bladder is not full

How ist bladder cancer diagnosed?

Bladder cancer is usually suspected after a patient presents with specific symptoms or after urine testing for other reasons. A diagnosis should be confirmed by exams and tests, which can also help to determine the stage of the cancer.

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy is usually performed in any case of suspected bladder cancer. A cystoscope, a thin instrument with a fibre-optic device or small camera on the end, is inserted through the urethra into the bladder. This method can be performed in a doctor’s office with the help of local anaesthesia to numb the urethra (reduce pain).

Bladder Biopsy

If an abnormal area is detected during cystoscopy, a biopsy (small sample of tissue) is taken. The tissue is sent to the laboratory, where it is examined by a pathologist. A biopsy can show whether cancer is present and what type of bladder cancer it is. If bladder cancer is detected, there are two characteristics that must be assessed.

Tumour stage (extent of disease, depth of invasion): The biopsy determines how deep the cancer has invaded the bladder wall. If the cancer is found in the tissue lining the inner surface of the bladder, it is called non-muscle-invasive, and a local treatment (usually surgical removal followed by intravesical treatment) is sufficient. If the cancer has already grown into the deeper layers of the bladder, it is called muscle-invasive, and a more aggressive treatment is needed.

Tumour grade (benign versus malignant tumour cell appearance): Bladder cancers are also assigned a grade, which refers to the appearance (differentiation) of tumour cells. This means the degree of how much tumour cells deviate from the appearance of normal cells. Low-grade cancers look more like normal bladder tissue. They are also called well-differentiated cancers. High-grade cancers look rather atypical. These cancers may also be called poorly differentiated or undifferentiated. High-grade cancers are more likely to grow into the bladder wall and to spread outside the bladder. These cancers are more difficult to treat.

Bladder cancer patients may develop more cancers in other areas of the bladder or the urinary system. For this reason, the doctor may take biopsies from several areas of the bladder and may order additional imaging procedures to see if there are additional tumours located in other areas of the urinary tract. The urinary collecting system comprises the renal pelvis and ureter (upper urinary tract), the urinary bladder and urethra (lower urinary tract).

How ist bladder cancer treated?

The choice of treatment of bladder cancer depends on the correct diagnosis. In early stages, if the tumour is found in the tissue lining the inner surface of the bladder (NMIBC), the first step of treatment is the surgical removal of the tumour(s), referred to as transurethral resection of the bladder tumour(s), abbreviated as TURBT. Under general anesthesia, the doctor inserts an endoscopic instrument through the urethra into the bladder and removes the tumour(s).

After the surgical removal, few tumour cells may remain in the bladder. If these are not treated, a new tumour may grow from them, and the bladder cancer may recur (disease recurrence). NMIBC has a relatively high tendency to recur. This relapse of disease (or recurrence) is also referred to as recurrent tumour(s), in contrast to the first occurrence of NMIBC, primary tumour(s).

To prevent or delay this recurrence, a drug is instilled into the bladder via a thin catheter after the surgical removal. This procedure is called intravesical instillation (also: adjuvant intravesical therapy). This treatment reduces the risk of new tumour development by eliminating remaining tumour cells or activating the immune system to fight those malignant cells. Depending on the exact diagnosis, there are different forms of instillation therapies.

If the cancer has already invaded deeper layers (muscle-invasive bladder cancer, abbrev. MIBC), the complete removal of the bladder must be considered. This surgical procedure is known as a radical cystectomy.